Gabrielle Andres

07 Feb 2023

SINGAPORE: Where Singapore gets its electricity from has been in the headlines in recent months, with the announcement that the country will import electricity from Malaysia and the opening of the largest energy storage system in Southeast Asia on Jurong Island.

Last Monday (Jan 30), it was announced that Singapore will import 100 megawatts (MW) of electricity from Malaysia as part of a two-year trial, under a joint agreement between YTL PowerSeraya and TNB Genco.

This marks the first time that electricity from Malaysia will be supplied to Singapore on a commercial basis.

Another agreement to import renewable energy from Laos was inked last year between Keppel Electric and Laos' state-owned Electricite du Laos (EDL).

Last month, Sun Cable – the company aiming to develop a A$30 billion (S$27.6 billion) project to supply solar power from Australia to Singapore via undersea cables – announced it was entering voluntary administration.

Questions asked online include why Singapore needs to import electricity and whether it can rely on solar energy.

CNA looks at Singapore’s power sources and where the country’s electricity could come from in the future.

Another agreement to import renewable energy from Laos was inked last year between Keppel Electric and Laos' state-owned Electricite du Laos (EDL).

Last month, Sun Cable – the company aiming to develop a A$30 billion (S$27.6 billion) project to supply solar power from Australia to Singapore via undersea cables – announced it was entering voluntary administration.

Questions asked online include why Singapore needs to import electricity and whether it can rely on solar energy.

CNA looks at Singapore’s power sources and where the country’s electricity could come from in the future.

WHERE DOES SINGAPORE GET ITS ELECTRICITY FROM?

About 95 per cent of Singapore’s electricity is generated from natural gas, which is the cleanest form of fossil fuel, as it produces the least amount of carbon emissions per unit of electricity.

Using natural gas has allowed Singapore to cut the amount of carbon it releases into the atmosphere.

According to government agency website Powering Lives, natural gas will “continue to be a dominant fuel for Singapore in the near future” as the country scales up other sources.

The percentage of natural gas used in electricity generation has increased from 19 per cent in 2000 to 95 per cent today, says the National Climate Change Secretariat Singapore (NCCS).

According to the Energy Market Authority's (EMA) figures, other energy products – including solar, biomass and municipal waste – accounted for 2.9 per cent, followed by coal at 1.2 per cent and petroleum products such as diesel and fuel oil at 1 per cent.

Singapore’s electricity is produced by the combustion of natural gas that is piped from Malaysia and Indonesia, NCCS said.

The country also diversified its supply of natural gas with the opening of a liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminal in Jurong Island, with plans to build a second terminal to support new industrial sites and power plants.

“This will not only provide critical mass for enhanced energy security, but it will also enable Singapore to be a hub for LNG-related business,” it said.

WHY DOES SINGAPORE NEED TO IMPORT ELECTRICITY?

The short answer is that Singapore lacks natural renewable energy sources, so importing energy allows it to access cleaner energy sources from abroad.

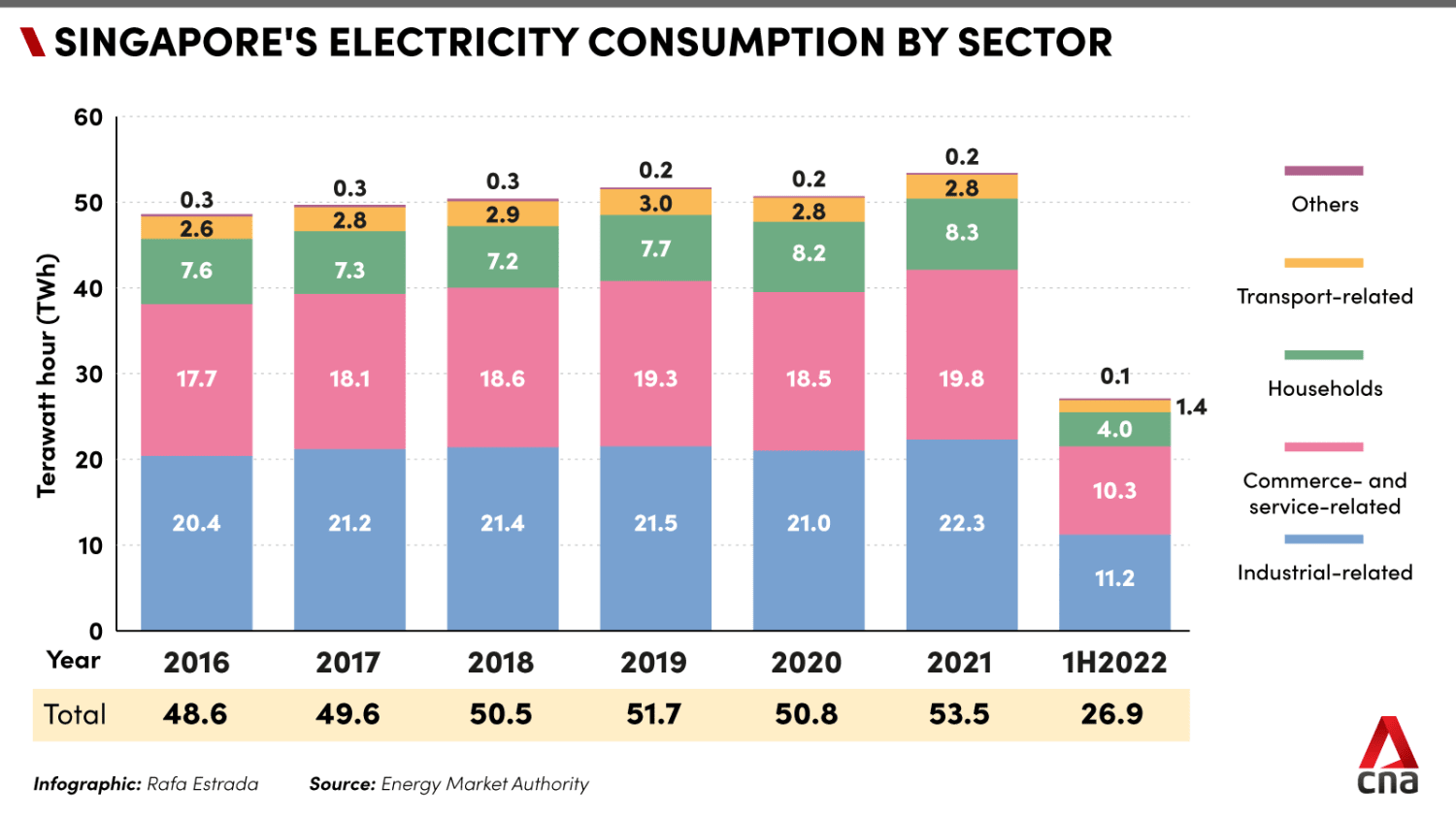

Singapore’s total electricity consumption has increased over the years.

It went up by 5.3 per cent from 2020 to 2021, with all sectors seeing a growth in its electricity consumption. Data from previous years also show a trend of growth.

The EMA has been working with various partners on trials to import electricity, which allows it to assess and refine the technical and regulatory frameworks. Countries involved include Malaysia, Indonesia and Laos.

Last year, Singapore started importing energy from Laos through Thailand and Malaysia, after a two-year power purchase agreement was signed between Keppel Electric and Laos’ state-owned EDL.

This was the first multilateral cross-border electricity trade involving four ASEAN countries, as well as the first renewable energy import into Singapore.

Under the agreement, the Lao PDR-Thailand-Malaysia-Singapore Power Integration Project (LTMS-PIP) will import up to 100MW of renewable hydropower using existing interconnections.

This is equivalent to about 1.5 per cent of Singapore's peak electricity demand in 2020, enough to power about 144,000 four-room HDB flats for a year.

It will also contribute to Singapore's sustainability goals under its Green Plan 2030 by tapping into the abundance of renewable energy from the region.

Regional power grids can help accelerate the development of renewable energy projects and promote economic growth and bring greater energy security to the region, according to a joint statement released by Keppel, EMA, the Laotian Ministry of Energy and Mines and EDL in June last year.

Additionally, the project serves as a "pathfinder" towards realising the broader vision of an ASEAN power grid, the agencies said.

"To overcome our land constraints, Singapore is tapping on regional power grids to access cleaner energy sources beyond its borders," added the EMA.

WHY CAN’T SINGAPORE JUST GO SOLAR?

Singapore is a tropical country, which means sunlight is one resource it has plenty of. The country has doubled its solar capacity since 2020, with more than 700 megawatt-peak (MWp) currently installed.

The country aims to increase solar capacity to at least 2 gigawatt-peak (2 GWp) by 2030, equivalent to powering about 350,000 households a year. This is expected to meet around 3 per cent of projected electricity demand.

Harnessing solar energy comes with its own set of challenges. For example, the amount of sunlight fluctuates depending on changes in cloud cover during the day. Solar panels are also unable to generate electricity at night.

Using solar panels requires space – something Singapore does not have much of. The EMA has acknowledged that there are limitations to the amount of solar energy that can be harnessed due to Singapore's limited land area.

As of the end of the first quarter of 2022, Singapore has a total of 5,455 solar panel installations, of which 3,564 are non-residential. About 48.9 per cent of the total installations are town council and grassroots units, followed by residential installations at 34.7 per cent and non-residential private sector at 13 per cent.

Installations from public service agencies constituted the remaining 3.5 per cent of total installations.

Other innovative ways to overcome the limited land area constraint are being trialled. For example, a new type of floating solar panel system is being piloted on Jurong Island.

Compared to conventional solar panel systems used in calmer water bodies such as reservoirs, the new system is designed to withstand stronger waves and rough sea conditions so that solar energy can be harnessed reliably, said Keppel Corporation in July last year.

Beyond land space constraints, energy storage systems are also being looked at.

Singapore deployed its first utility-scale energy storage system in October 2020, with a capacity that can power more than 200 four-room HDB units for a day.

Last week, the largest energy storage system in Southeast Asia was opened on Jurong Island.

The Sembcorp Energy Storage System has a maximum storage capacity of 285 megawatt-hours (MWh), enabling it to meet the electricity needs of about 24,000 households in four-room HDB flats for one day in a single discharge.

The deployment of the utility-scale facility means that Singapore has achieved its 200 MWh energy storage target ahead of time. Singapore previously announced a target of deploying at least 200 MWh of energy storage systems beyond 2025 as part of the Singapore Green Plan 2030.

THE FUTURE OF SINGAPORE’S ENERGY

In October last year, Deputy Prime Minister Lawrence Wong announced that Singapore will raise its climate target to achieve net-zero by 2050 as part of its long-term low emissions development strategy.

According to EMA, solar energy remains the most promising renewable energy source in the near term for Singapore.

In fact, Singapore achieved its 2020 solar target of 350 megawatt-peak (MWp) in the first quarter of that year. Singapore is also working towards achieving a new solar target of at least 2GWP by 2030.

Solar energy is one of EMA's "four switches" vital to decarbonising Singapore – the others being natural gas, regional power grids and low-carbon alternatives.

Singapore plans to import up to 4GW of low-carbon electricity by 2035, which could make up around 30 per cent of Singapore's projected electricity supply then.

Steps are also being taken to diversify import sources and ensure back-up supply is in place to mitigate disruptions.

The LTMS-PIP is one of the trials that the EMA has been working on as part of plans to realise a regional power grid.

Another of the four switches is emerging low-carbon alternatives. Singapore is exploring low-carbon technologies such as hydrogen and carbon capture, as well as utilisation and storage technologies.

"While such technologies are nascent, the Government is taking active steps including investing in (research and development) through the Low-Carbon Energy Research (LCER) Funding Initiative," said the EMA.

Two years ago, S$55 million was awarded to 12 projects to research low-carbon technologies. An additional S$129 million has been committed by the Government for Phase 2 of the LCER programme.

Over the last 50 years, Singapore has moved from oil to natural gas for cleaner power generation. EMA said it is reviewing emissions standards for fossil fuel-fired generation units. The authority expects to introduce the revised standards in 2023.

It also said it will continue to diversify its natural gas sources and work with power generation companies to improve power plant efficiency.

Under the Singapore Green Plan 2030, Singapore also aims to have best-in-class generation technology that meets heat-rate/emissions standards and reduces carbon emissions, as well as a diversified electricity supply with clean electricity imports.

---------------

Commentary: Why is sunny Singapore not covered with rooftop solar panels?

In land-constrained Singapore, rooftops provide the most readily available space for the rollout of solar panels, but there are many barriers to deploying more of them, say Reed Smith’s Matthew Gorman and Miriam Bandera.Matthew Gorman

Miriam Bandera

04 Jul 2022

SINGAPORE: Rising fuel prices and other costs of living have delivered a stark reminder of how reliant we are on oil and gas, making the transition to renewable energy even more urgent.

However, Singapore authorities are confident they can pull it off. The Energy 2050 Committee Report published by the Energy Market Authority (EMA) in March concluded it is “technically viable” for Singapore’s power sector to achieve net zero emissions by 2050.

One of the strategies identified is to maximise solar deployment and use energy storage systems to manage solar intermittency.

Solar energy from photovoltaic (PV) systems is currently considered the most viable renewable energy source available to Singapore. It is one of the EMA’s “four switches” vital to decarbonising Singapore – the others being natural gas, regional power grids and low-carbon alternatives.

Yet, despite this recognised potential, some argue solar power will play a limited role in the country’s road to net zero. In a 2020 report, the Solar Energy Research Institute of Singapore (SERIS) estimated Singapore has the potential to deploy up to 8.6 Gigawatt-peak (GWp) of solar energy by 2050 – around 10 per cent of the nation’s projected electricity demand then.

So, if solar can only contribute 10 per cent of Singapore’s electricity demand by 2050 in the best-case scenario, why put so much effort into optimising the sector?

It bears remembering that other forms of renewable energy, such as wind, tidal and hydro, are not an option in Singapore. In this context, extracting every ounce of potential from solar becomes a more significant feature of Singapore’s net zero goal.

THE QUESTION OF STORING SOLAR ENERGY

Variability is a key barrier to solar energy becoming a significant source of power in Singapore. Solar PV panels are unable to generate electricity at night and, even during the day, the availability of sunlight in Singapore fluctuates due to frequent changes in cloud cover.

For power to run when it’s dark out, solar energy storage technologies need to be scaled up and utilised more cohesively. While batteries are used to store solar-generated electricity on a localised basis, the true challenge lies in developing efficient and reliable utility-scale assets that can manage storage across an entire power grid.

The good news is that these solutions exist and are being deployed. According to figures from the trade body American Clean Power Association, utility-scale battery energy storage system installations in the US grew 196 per cent in 2021.

Closer to home, Singapore deployed its first utility-scale energy storage system in October 2020, with a capacity that can power more than 200 four-room HDB units in one day.

The system not only participates in the wholesale electricity market but also provides insight into the performance of energy storage systems in heat and humidity, and will aid the establishment of technical guidelines.

Singapore’s evolving solar landscape can be compared to ongoing efforts for self-sufficiency in its water supply. It is not that we do not have enough rainfall to meet our needs, but rather that the infrastructure for capturing, storing, distributing and recycling rainfall has to be up and running to realise its full potential. Public education and technology must also go towards minimising waste.

DEPLOYING SOLAR PV ON ROOFTOPS TO OPTIMISE LIMITED LAND

A second obstacle to a significant increase in the level of electricity generated from solar PV in Singapore is space. Singapore is a heavily built-up city, which already faces multiple competing demands for land.

According to the EMA, as of March 2021, there were 4,585 grid-connected solar PV installations in Singapore. Their total capacity amounts to an around 443-megawatt peak (MWp), with the private sector contributing most of it (53 per cent), followed by town councils and grassroots units (38 per cent).

There are other technologies for optimising what little space Singapore has for solar panels. These include mobile solar PV systems that can be used on temporarily vacant land and relocated as necessary, and building-integrated PV in which solar panels are incorporated into a building’s facade.

While most of these installations are on rooftops, floating solar PV facilities could contribute significantly to solar PV capacity. The 60MWp Tengeh Reservoir plant, launched in July 2021, can power 16,000 four-room HDB flats and reduce emissions equivalent to taking 7,000 cars off the road. Other floating projects are in the pipeline.

But rooftops still provide the most readily available space for large-scale rollout. According to the 2020 SERIS report, the total net usable area for rooftop PV deployment in Singapore is approximately 13.2 sq km.

In contrast, the space for building facade PV, mobile/land-based PV and floating PV is more limited, at 9.8 sq km, 5.0 sq km and 4.6 sq km respectively.

Installing solar panels on existing rooftops and facades is therefore the most viable near-term option for maximising solar PV deployment in Singapore. Buildings can install enough PV panels and a localised energy storage system to provide electricity for the building’s occupants round-the-clock, which goes towards saving utility costs in the long run.

If the building generates a viable amount of excess power, it can be exported to the grid – for potential revenue. SP Group has schemes for businesses and homeowners where they can receive payment for excess solar electricity sold to the grid.

A second obstacle to a significant increase in the level of electricity generated from solar PV in Singapore is space. Singapore is a heavily built-up city, which already faces multiple competing demands for land.

According to the EMA, as of March 2021, there were 4,585 grid-connected solar PV installations in Singapore. Their total capacity amounts to an around 443-megawatt peak (MWp), with the private sector contributing most of it (53 per cent), followed by town councils and grassroots units (38 per cent).

There are other technologies for optimising what little space Singapore has for solar panels. These include mobile solar PV systems that can be used on temporarily vacant land and relocated as necessary, and building-integrated PV in which solar panels are incorporated into a building’s facade.

While most of these installations are on rooftops, floating solar PV facilities could contribute significantly to solar PV capacity. The 60MWp Tengeh Reservoir plant, launched in July 2021, can power 16,000 four-room HDB flats and reduce emissions equivalent to taking 7,000 cars off the road. Other floating projects are in the pipeline.

But rooftops still provide the most readily available space for large-scale rollout. According to the 2020 SERIS report, the total net usable area for rooftop PV deployment in Singapore is approximately 13.2 sq km.

In contrast, the space for building facade PV, mobile/land-based PV and floating PV is more limited, at 9.8 sq km, 5.0 sq km and 4.6 sq km respectively.

Installing solar panels on existing rooftops and facades is therefore the most viable near-term option for maximising solar PV deployment in Singapore. Buildings can install enough PV panels and a localised energy storage system to provide electricity for the building’s occupants round-the-clock, which goes towards saving utility costs in the long run.

If the building generates a viable amount of excess power, it can be exported to the grid – for potential revenue. SP Group has schemes for businesses and homeowners where they can receive payment for excess solar electricity sold to the grid.

ROOFTOP SOLAR PV STILL HAS TO COMPETE FOR SPACE

The rollout of solar PV installations on rooftops and facades needs to be weighed against other considerations as Singapore adopts a more holistic approach to sustainability.

The Government has made clear that solar PV will not be undertaken at the expense of greenery, green spaces and biodiversity. Under the Sustainable Singapore Blueprint, there are plans for 200 hectares of skyrise greenery on Singapore’s buildings by 2030.

This goal may compete with the deployment of rooftop solar PV, for example in predominantly residential areas where a greater amount of greenery is proposed.

How soon can sustainable homes become a reality, how much would they cost and what about the challenge of retrofitting old buildings? CNA's The Climate Conversations takes a closer look:

Another barrier to rooftop solar PV deployment arises from the competition for space on roof surfaces from other important uses such as water tanks, elevator shafts, air-conditioning facilities, parking and recreational spaces reserved for tenants.

While the competition from some of these uses can be mitigated through technology and more creative building designs, they nevertheless remain a constraint on rooftop solar PV systems. This effect is likely more acute in older buildings which were not designed with solar PV installations in mind.

Nonetheless, rooftop solar will play an important part in realising both Singapore’s net zero emissions target and energy security.

Taking into account the price shocks in oil and gas over recent years and the cost efficiencies being driven by technological improvements in PV panels, inverters and other components, there are reasons to be positive about the future of rooftop solar.

Matthew Gorman is a Partner and Miriam Bandera is an Associate at Reed Smith, Singapore.

Source: CNA/geh

No comments:

Post a Comment