|

| New research suggests that China’s population will hit a high of 1.41 billion people in 2023. Photo: Xinhua |

Finbarr Bermingham

2 May, 2019

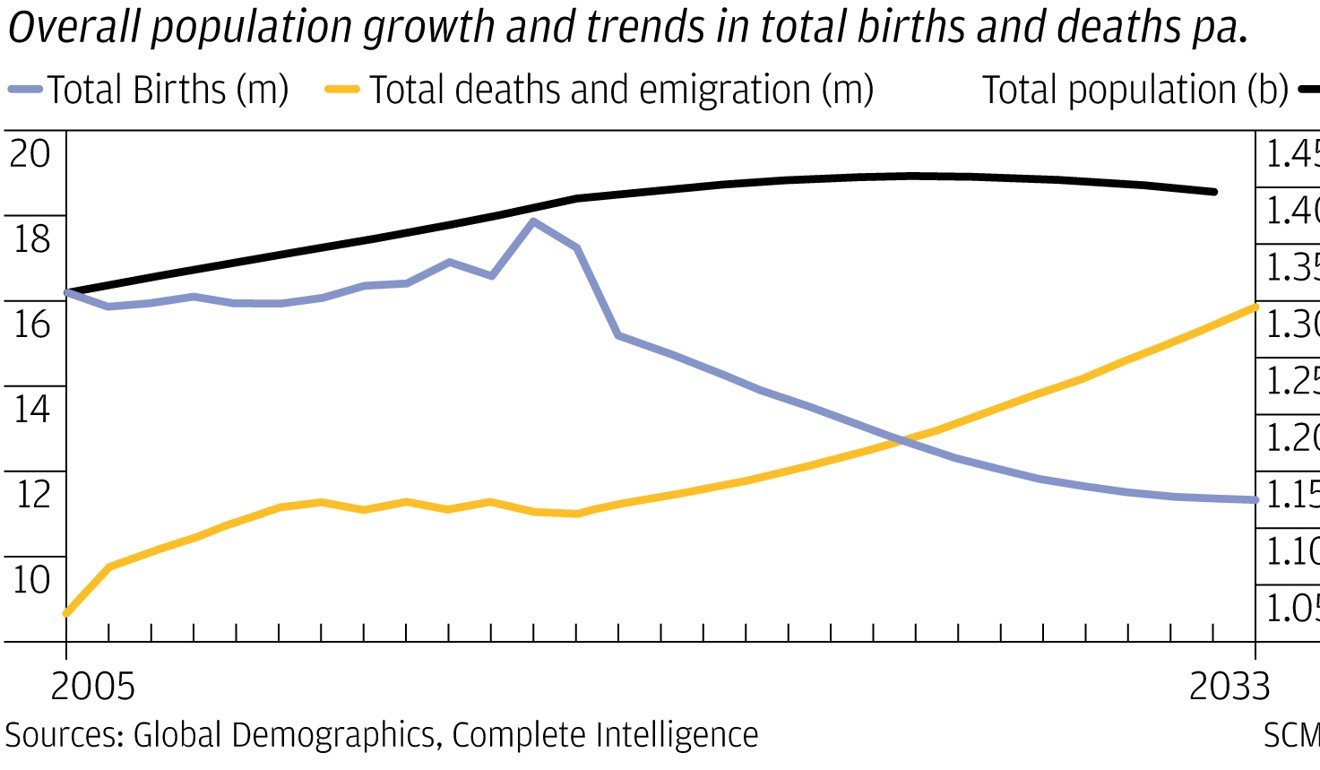

China’s population will peak in 2023, five years earlier than official forecasts, according to a new report.

Tony Nash, CEO and founder of Complete Intelligence, one of the co-authors of the report, said the findings should be a cause for concern for Beijing’s policymakers, who waited too long to lift the controversial one-child policy for its rapidly greying society.

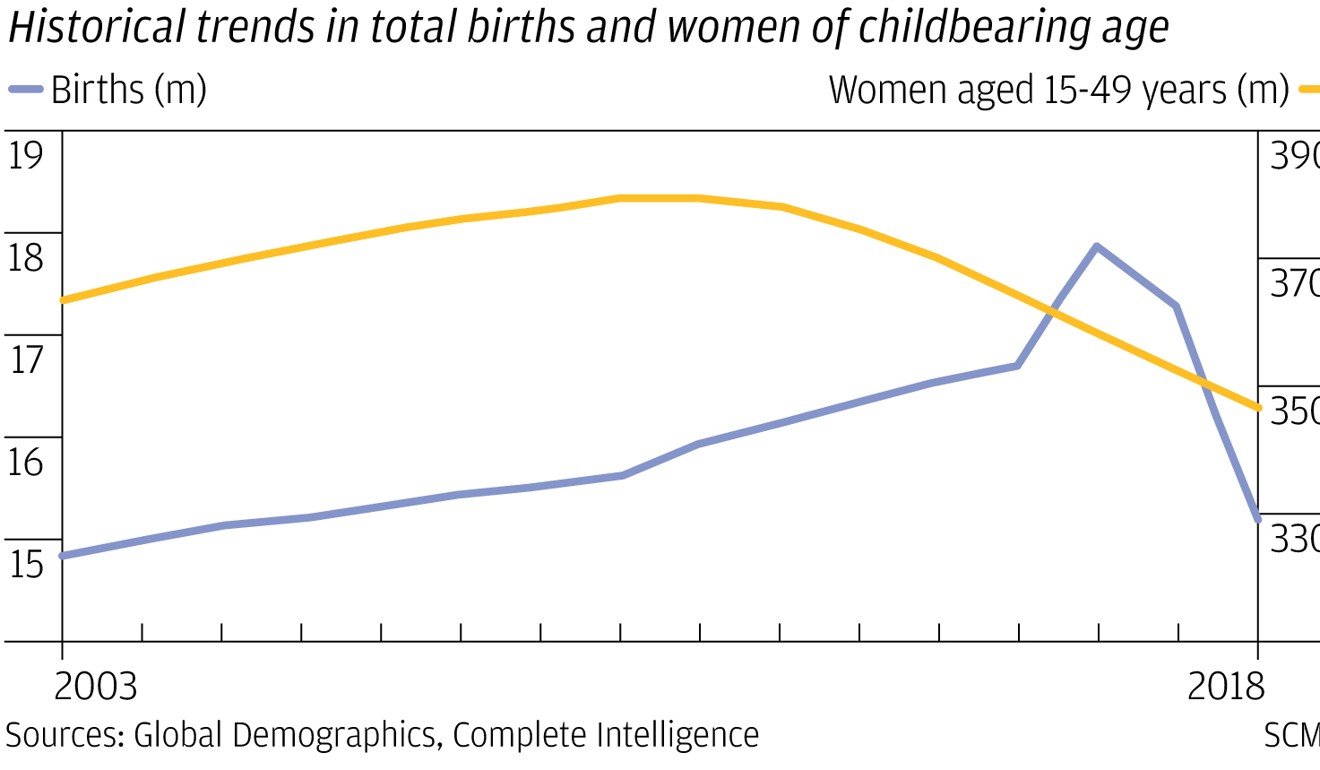

China abandoned the policy in 2015 to allow couples to have two children. But the birth rate last year fell to its lowest since 1961, indicating that most, if not all, of those parents who wished to have a second child already had done so, the study found.

“At a macro level, it means China’s peak population moves forward from 2028 to 2023, when the population hits 1.41 billion persons,” the report, co-authored by Global Demographics, said.

The report said a major driver in the falling birth rate was the decline in the number of women of child-bearing age, with the population of those women – aged between 15 and 49 – expected to decrease by 56 million between 2018 and 2033.

The forecasters said there would be 27 million fewer children aged nine or younger by 2028, a 17 per cent reduction from today, putting a damper on related consumer markets including toys, clothing, milk-based products, education and childcare.

It estimated that the population of preschool-aged children – those up to age four – peaked in 2017 at 84 million. The annual decline in this age group would be 2.8 per cent, the authors estimated, with the size of the group shrinking to 57.4 million in 2033.

The findings are broadly in line with those of other demographers.

Chen Youhua, a professor from Nanjing University’s school of social and behavioural sciences, said that while different forecasters would have roughly different numbers, peak population in the medium term was inevitable.

“A lot of research from different international institutions, including mine, estimate that China’s population will stop increasing at around 2025 and then start falling ... From the demographic point of view, the real challenge for China will arrive soon after 2025,” Chen said.

The research suggests that China might struggle to realise its leaders’ ambition to become “rich before it gets old”, particularly with economic growth already starting to slow.

Richard Jackson, president and founder of the Global Ageing Institute, said China was going to grow old before it grew rich.

“And that is the unintended consequence of the one-child policy – the fact that the birth rate in China is below replacement,” Jackson said.

“The great majority of the population still depends significantly on the extended family for support. This is challenging when you have shrinking family sizes. You have this gender imbalance and a slowing economy. It all acts as a kind of multiplier on the underlying stresses of development.”

Heilongjiang province in China’s norther rust belt, is expected to suffer the biggest decline in population, with a 5.2 per cent shrinkage, followed closely by the provinces of Liaoning, Zhejiang and Jilin, according to the report.

The findings correlate roughly with other studies of China’s declining population, such as an

analysis of satellite imageryconducted by Tsinghua University earlier this year, which showed that light intensity had dimmed in 28 per cent of 3,300 Chinese cities and towns between 2013 and 2016.

Many of these urban areas were scattered among China’s rust belt in its northeast, where local governments are still spending heavily on debt-fuelled infrastructure projects, despite their dwindling populations and slowing economies.

Nash, from Complete Intelligence, said growing affluence was part of the reason behind the declining population, with wealthier families having fewer children. But the decline was cause for concern.

“Everything from providing education to government services to manpower, these are all things that matter in a big way when you hit peak population,” he said.

“They waited too long to lift the one-child policy. Had the one-child policy been lifted in say 2005, I think you would have had a vibrant, growing birth rate, but they waited a decade too long.”

However, Clint Laurent, managing director of Hong Kong-based Global Demographics, said greater affluence would bring social stability, while better health care would mean people would live and work for longer, partly countering the effect of an ageing society.

“This has not happened by accident. The Chinese government is smart, no matter what you might think of them politically. They've got some brains there and it's stabilising the population,” Laurent said. “If you have a good proportion of the population that work, their affluence goes up, they have better lifestyles, you have social stability and, and that is really what China has planned for. And that is really what it's moving into quite nicely.”

Additional reporting by Sidney Leng

This article appeared in the South China Morning Post print edition as: China’s population ‘on course to peak in 2023, not 2028’

No comments:

Post a Comment