By Tom Holland

6 Aug 2016

South China Morning Post

Facing a deep slowdown after years of investment-fuelled growth that culminated in a huge property and stock market bubble, the leaders of Asia’s largest economy come up with a cunning plan. By launching an initiative to fund and construct infrastructure projects across Asia, they will kill four birds with one stone.

They will generate enough demand abroad to keep their excess steel mills, cement plants and construction companies in business, so preserving jobs at home. They will tie neighbouring countries more closely into their own economic orbit, so enhancing both their hard and soft power around the region. They will further their long term plan to promote their own currency as an international alternative to the US dollar. And to finance it all, they will set up a new multi-lateral infrastructure bank, which will undermine the influence of the existing Washington-based institutions, with all their tedious insistence on transparency and best practice, by making more “culturally sensitive” soft loans. [i.e. bribes] The result will be the regional hegemony they regard as their right as Asia’s leading economic and political power.

If you think you’ve seen this movie before, you probably have. That could be an outline of China’s “One Belt, One Road” initiative, launched last year to great fanfare, and relentlessly promoted by loyal officials ever since. But it’s actually a description of a strikingly similar plan rolled out by Japanese prime minister Keizo Obuchi in the 1990s. That too promised to provide work for Japan’s recession-hit construction sector by building Japanese-funded infrastructure projects around Asia. And it even included a proposal – never realised – to establish an Asian Monetary Fund to lend to regional governments on easier terms than either the IMF or World Bank.

Unfortunately for Beijing, the precedent is hardly encouraging. From the start the scheme was plagued by bickering over conditions and allegations of corruption. A handful of infrastructure projects did get built, but the reality fell woefully short of Tokyo’s grandiose dreams. Far from cementing Japan’s economic ascendancy across Asia, the project left a legacy of bad blood, and marked the beginning of a financial retreat from around the region that Japan has only recently begun to reverse.

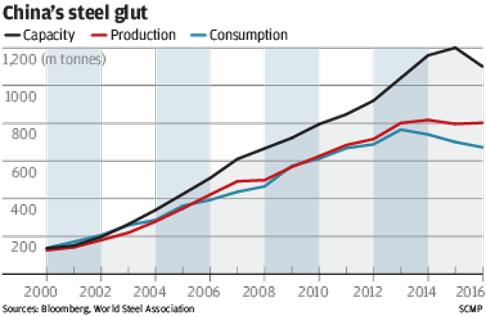

All the signs are that China’s One Belt, One Road plan will similarly fail in its main objectives. First, the idea that infrastructure projects in Central and South East Asia could absorb a sizeable portion of China’s excess industrial capacity is simply unrealistic. Consider steel. Currently China’s steel mills can turn out some 1.1 billion tonnes of the metal annually. Yet even with economic stimulus efforts in full swing, no one expects domestic demand to exceed 700 million tonnes this year. It is hard to imagine China building enough roads, ports and pipelines across Asia to use up the extra 300 million tonnes of capacity, especially when you consider that the World Steel Association forecasts demand in the European Union, the world’s largest economy, to be just 150 million tonnes this year.

Beijing could try. But if it did, it would run into another problem. Asia needs infrastructure development, but the region’s capacity to absorb new projects is limited. As China has learned at home, building a new high speed rail line or state of the art airport is easy enough given plentiful funding. But building a high speed rail line that is economically viable is altogether more difficult. Inevitably, if Beijing attempts to pursue projects at a pace and in a number sufficient to make a dent in its excess capacity, it will end up building white elephants, wasting money, and encouraging corruption on a scale never before seen.

These constraints mean China’s ambition of using lending tied to the One Belt, One Road initiative to help promote the yuan as Asia’s international currency of choice is also destined to fail. What policy-makers had in mind was something akin to the Marshall Plan, by which the United States pumped money into Western Europe in the late 1940s to fund post-war reconstruction, so confirming the US dollar’s position as the world’s dominant reserve currency. But 1940s Europe was very different from Central Asia today. Europe’s physical infrastructure may have been destroyed by war, but its know-how and institutional strength in depth were largely intact. Rebuilding on such foundations was relatively straightforward.

Developing Asia’s foundations are still under construction. But while physical capital like a new port or railway can be built in just a few years, building the human and institutional capital that allow that port to operate efficiently and to contribute effectively to economic and social progress is a slower process. The two need to go hand in hand, which is why multi-lateral lenders like the World Bank lay such heavy stress on best practice. The senior officials charged with implementing China’s grand plan appreciate these capacity constraints, and appear to be scaling down their ambitions. That’s sensible, but it means the One Belt, One Road initiative will fall far short of its original objectives, just as its Japanese forerunner did almost 20 years ago.

[BUT...]

Why you shouldn’t believe the horror stories about China’s economy

Sceptics paint a bleak picture, but Beijing has many tools at its disposal to combat worst-case scenarios

By Tom Holland

9 Jan 2017

Everyone loves a horror story, and there are a number of real chillers doing the rounds just now about China, the yuan, and the looming risk of a financial collapse. These stories differ in detail, but generally they share a similar plot. It goes something like this: rich Chinese are losing faith in their economy and the yuan. As growth slows and debt mounts, Chinese fearful of an impending crisis are shifting their wealth offshore and into foreign currencies. These outflows are putting pressure on the yuan, which is weakening in response. In turn this weakness is prompting more and more mainland Chinese to try to preserve their capital by seeking safety in foreign currencies. The result is a self-reinforcing feedback loop that threatens to precipitate the very crisis those fleeing the yuan hope to escape.

It’s a gripping tale. Happily, like all good horror stories, it springs more from imagination than from fact.

That’s not to say it has no basis at all in reality. Clearly China’s growth is slowing, debt does continue to rise relative to gross domestic product, the yuan’s exchange rate against the US dollar did weaken last year, and the domestic economy has seen net capital outflows.

But none of this portends the imminent financial death spiral the more blood-curdling China-sceptics describe.

Yes, China’s growth has slowed as the easy gains from playing catch-up with more developed economies have been exhausted. Yes, total debt has ballooned to somewhere around 250 per cent of GDP, up from 150 per cent following the financial crisis, with much of the capital misallocated to unneeded steel mills, uninhabited ghost cities, and unwanted white elephant infrastructure projects.

And yes, as a result, the returns earned by real economy investments have deteriorated.

It is also true that the yuan has weakened against the US dollar. Between the beginning of 2014 and the end of 2016, the Chinese currency declined 13 per cent. And it is true that wealthy Chinese have sought to ship money offshore. Even though Beijing still maintains controls on cross-border capital flows, the inventive have found numerous ways around the restrictions. These have ranged from buying a gold Rolex in Macau on a UnionPay debit card and immediately pawning it, to – at the other end of the scale – buying trophy assets like New York hotels or English Premier League football clubs under the guise of outward direct investment.

But both the extent of the yuan’s decline and the scale of capital flight have been exaggerated.

Over the last three years, while the yuan has fallen 13 per cent against the US dollar, the Canadian dollar has fallen 20 per cent, the British pound has dropped 21 per cent, and the euro has slumped 24 per cent. In other words what we have seen is not broad-based yuan weakness, but US dollar strength. In fact, over the last six months, the yuan has remained stable against the People’s Bank of China’s (PBOC) reference basket of currencies.

Similarly, the drawdown in China’s foreign reserves from almost US$4 trillion in mid-2014 to roughly US$3 trillion today has been overstated. If we assume that China held half its foreign reserves in non-US dollar currencies, then the 28 per cent appreciation of the US dollar against a basket of major currencies implies that the US dollar value of the non-US portion of China’s reserves would have fallen by US$438 billion even without any drain on the reserve pot.

As a result, net outflows have been much smaller than the fall in headline reserves. In November, for example, the net outflow was closer to US$40 billion than the US$69 billion that the slump in the US dollar value of China’s reserves suggested.

Still, US$40 billion is a lot of money to watch going out the window in a single month. Despite that, there is little evidence that capital flight is gaining pace. The recent increase in net outflows is not the result of a pickup in flight capital. Instead it has largely been caused by a slowdown of inflows into the yuan as Chinese exporters have retained their revenues offshore to take advantage of the US dollar’s strength.

Of course, if there were to be a marked acceleration in outflows from here and a steep fall in the yuan, the combination could badly dent confidence in Beijing’s ability to maintain financial stability.

However, the authorities have plenty of tools available to forestall any such run on the yuan. In recent weeks they have tightened their scrutiny both of individual foreign exchange purchases and of outward investments by Chinese companies. There is talk that the government is twisting the arms of state-owned companies to repatriate foreign currency earnings held offshore. And on Thursday the PBOC engineered a liquidity squeeze in the Hong Kong market that saw the overnight interest rate on offshore yuan hit 80 per cent – more than enough to deter any foreign players planning to borrow the currency in order to sell it short.

In a nutshell, the scare stories about the devastating consequences of a weakening yuan and gathering capital flight are just that: stories.

The spectre of a financial crisis in China – at least this year – is illusory, nothing more than a figment of the storytellers’ overactive imaginations.

Tom Holland is a former SCMP staffer who has been writing about Asian affairs for more than 20 years

Of course, if there were to be a marked acceleration in outflows from here and a steep fall in the yuan, the combination could badly dent confidence in Beijing’s ability to maintain financial stability.

However, the authorities have plenty of tools available to forestall any such run on the yuan. In recent weeks they have tightened their scrutiny both of individual foreign exchange purchases and of outward investments by Chinese companies. There is talk that the government is twisting the arms of state-owned companies to repatriate foreign currency earnings held offshore. And on Thursday the PBOC engineered a liquidity squeeze in the Hong Kong market that saw the overnight interest rate on offshore yuan hit 80 per cent – more than enough to deter any foreign players planning to borrow the currency in order to sell it short.

In a nutshell, the scare stories about the devastating consequences of a weakening yuan and gathering capital flight are just that: stories.

The spectre of a financial crisis in China – at least this year – is illusory, nothing more than a figment of the storytellers’ overactive imaginations.

Tom Holland is a former SCMP staffer who has been writing about Asian affairs for more than 20 years

No comments:

Post a Comment