The New York Times

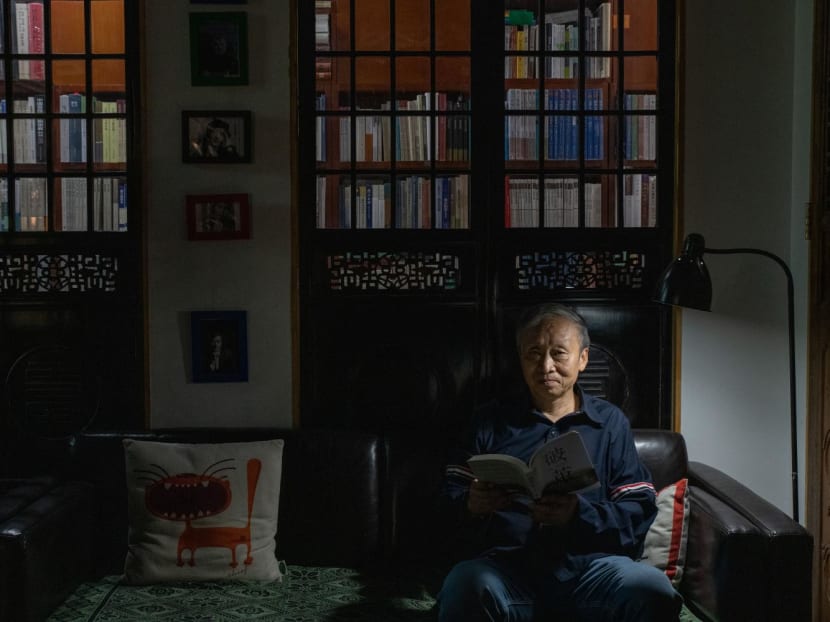

Mr Wang Xiaodong, a writer once called the standard-bearer of Chinese nationalism, at a bookstore in Beijing on Sept 1, 2022.

October 27, 2022

BEIJING — Mr Wang Xiaodong once gave a speech declaring that “China’s forward march is unstoppable”. He published essays calling on China to build up its military. He co-wrote a book, bluntly titled “China Is Unhappy”, in which he said the country should aim to control more land and shape global politics. “We should lead this world,” he said.

Now, Mr Wang, a 66-year-old Beijing-based writer once called the standard-bearer of Chinese nationalism, has another message: That nationalism has gone too far.

For years, it was Mr Wang whom many Chinese dismissed as too radical, as he railed that the Chinese establishment was too beholden to Western ideas and global trade, too content to let China ease into a world order rigged by the United States.

Then, as China grew more powerful, his message championing nationalism — and his combative, only-idiots-disagree-with-me style — found a following. His book became a best seller. Today, swagger about the country’s greatness is a staple of Chinese public conversation, from diplomatic declarations to social media chatter.

But rather than revelling in that success, Mr Wang has become alarmed by it. Egged on by government propaganda, Chinese nationalism has become increasingly volatile and vitriolic. And so Mr Wang has found himself in the unexpected position of trying to tamp down the movement that he helped ignite nearly 35 years ago.

To his millions of social media followers, he now opines that excessive self-regard imperils China’s rise, which he no longer calls inevitable. In blog posts and videos infused with a professorial — some say lecturing — demeanor, he warns that cutting off relations with the United States would be self-defeating. He lashes out at other nationalist influencers, accusing them of stoking extreme emotions to win followers.

Now, this pioneer of nationalist bravado is the one fending off criticisms of being too moderate, too cozy with the West, even a traitor.

Mr Wang, who in person is warmer than his public persona might suggest, has greeted the reversal with a mixture of astonishment and amusement.

“They’ve forgotten, in the past few decades, I’ve been called nationalism’s godfather. I created them,” he said in an interview over tea and steamed fish at a Shanghainese restaurant near his home in Beijing. “But I never told them to be this crazy.”

The divide may be, in part, generational. For young people who have known only an ascendant China, a strident posture toward the rest of the world may feel natural. Other older public figures have raised similar concerns to Mr Wang; DrYan Xuetong, an often-hawkish international relations professor, lamented this year that students held an overly confident, “make-believe” mind-set about China’s global stature.

China’s humbler history has been central to Mr Wang’s worldview.

Born to well-educated parents — his father was an engineer, his mother a teacher — he was 10 when Mao Zedong launched the Cultural Revolution. Mr Wang’s school closed for two years; he read old textbooks on his own.

That tumultuous period instilled in Mr Wang a lasting pugnaciousness. Unsupervised, he and his friends frequently brawled with other young people. “It made me feel very self-righteous — I could fight like that, without any punishment,” he said, with a smirk familiar to viewers of his videos. “That was not necessarily a great lesson for me.”

After the Cultural Revolution ended, Mr Wang enrolled at Beijing’s prestigious Peking University to study math — an educational pedigree this unapologetic elitist frequently invokes.

But Mr Wang’s attention quickly slipped from classes. The 1980s were a heady time of new ideas and national soul-searching, as the country distanced itself from Mao’s suffocating reign. Mr Wang began devouring foreign novels, becoming more accessible as China opened its economy. He practiced English by listening to Voice of America and reading Reader’s Digest.

Soon, though, he would decide China’s interest in the West had gone too far.

He traces his first major brush with nationalism to 1988, when the state broadcaster aired a documentary, River Elegy, which blamed China’s backwardness on its traditional civilisation and urged the country to learn from Japan and the West. Mr Wang, by then working as a young economics professor, was outraged. He wrote a short essay criticising the series as self-loathing — an idea he would later dub “reverse racism”.

It was a bold argument, given the documentary’s imprimatur of state approval. Mr Wang said he was able to publish it only by pleading with an editor at the newspaper China Youth Daily, which ran it not in the politics section but in the lower-profile entertainment pages.

It aroused intense debate anyway. And it made Mr Wang a leading voice of Chinese nationalism, a movement that was gaining momentum as the broader political atmosphere changed. After the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, the government turned on the political openness of the 1980s and became more guarded toward the outside world.

Mr Wang was there to cheer it on — and to argue that it didn’t go far enough.

He churned out increasingly provocative books and essays, arguing that China should become more militant to survive American hegemony. He said China’s huge population demanded more resources — which might not be attainable through peaceful means alone.

In “China Is Unhappy”, published in 2009, he called those who said China was not ready to take on the United States “slaves” who “glorified peace”.

The book climbed a best-seller list, earning international headlines. But in a sign that China was still negotiating its relationship to nationalism, the book was also widely criticised. Liberal intellectuals accused it of poisoning and militarising China’s youth. Xinhua, the state news agency, quoted readers’ reviews calling it “poor and radical”.

That uneasiness would soon dissipate. As China’s hosting of the Beijing Olympics in 2008 fuelled a new national confidence, Mr Wang at first was thrilled. He was especially excited by how the internet helped those ideas spread, arguing it proved the organic appeal of nationalism — and his own ideas.

But gradually, that sense of vindication turned to concern.

Tensions between China and the West intensified as trade deficits soared and China’s military began flexing its new muscles in places like the South China Sea.

The animus then spiked after the outbreak of the coronavirus, and some social media users began cheering the idea of severing economic ties with the United States, bragging that China could go it alone. Even cultural exchange became a target: users attacked vegetarianism as a foreign import, or questioned people for cosplaying in kimonos.

Mr Wang — a self-declared fan of American TV, especially “Westworld” and “Game of Thrones” — began worrying that many Chinese had swung too far, from self-deprecation to imagined invincibility. He admitted to having been overly optimistic himself about the pace of China’s development in his earlier writings, and said the country was still not as powerful as the United States.

“Before, Chinese people’s self-esteem was too low, and they thought China couldn’t do anything right,” Mr Wang said. “Now, they think China is No. 1 and can fight anyone — and I can’t take that either. China isn’t that strong yet.”

As had become his habit, he aired those views on the Twitter-like platform Weibo, where he has 2.5 million followers.

Last December, he posted a video arguing that China should do whatever was necessary to remain part of global trade, even if that meant enduring some humiliation.

“I used to express some different views,” Mr Wang acknowledged in the video, seated before his usual backdrop of elegant carved wooden cabinets. But, he continued, “we really haven’t gotten to the point where we win at everything we do”.

This summer, after some social media users predicted that China would shoot down House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s plane to Taiwan, Mr Wang said too much bluster made China appear weak.

In turn, he is tarred by commenters as an arrogant has-been, and he seems to relish hitting back, with condescension. When one user told Mr Wang to go to America, he responded, “Idiots like you not only lack brains, you also lack morals.”

There is one notable omission from his list of targets. He almost never criticises the government, which arguably has done more than anybody to foment nationalism, through its aggressive “Wolf Warrior” diplomacy and disinformation campaigns about foreign countries.

Mr Wang said he deliberately avoided direct commentary on domestic politics, focusing instead on social media users’ reactions to certain issues, because he worried about his social media accounts being shut down; he earns money through paid subscribers. He now tries to comment more on international affairs. Many of his latest videos are about the war in Ukraine. “I’m actually quite timid,” he joked.

Still, if Mr Wang comes off as moderate today, that is perhaps only because of how extreme Chinese online nationalists have become. He still champions a superpower China; his quibble is over tactics and timing. At times, he has joined the online masses in mobilising against the West, such as when he cheered a boycott of Nike and H&M for swearing off Xinjiang cotton.

Mr Song Qiang, one of Mr Wang’s four co-authors on “China is Unhappy”, said Chinese nationalism today was a clear descendant of the movement Mr Wang had helped start, and shape.

“The national awakening that began with Wang Xiaodong’s criticism of ‘River Elegy’” — the 1988 documentary — “has become mainstream,” said Mr Song, who added that he disagreed that young nationalists were irrational. “There’s no reason to say that the nationalism inherited by the new generation is different from that of the 1990s.”

Still, Mr Wang knows his popular appeal may be diminishing, given how the broader political climate rewards more aggressive chest-thumping than he might think wise.

But he believes his views will retain an audience — at least for now.

“Let’s put it this way: Right now, it’s my generation that’s in charge, not theirs,” he said of younger Chinese. “We’ll see what happens after we die.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

No comments:

Post a Comment