[Note: This is a Time interview from 2015, after the passing of Lee Kuan Yew.]

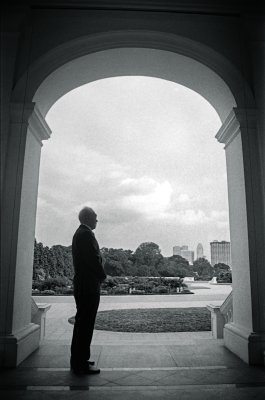

Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong addresses the nation about the passing of his father, Singapore's founder Lee Kuan Yew, during a live broadcast on Monday, March 23, 2015, in Singapore

Terence Tan—AP

By Hannah Beech

Zoher Abdoolcarim

July 23, 2015

As Singapore gears up to celebrate the 50th anniversary of its independence, the city-state once dismissed as a “little red dot” at the midpoint of regional maps now serves as the epicenter of Asian-style development. By combining Confucian values with state-sponsored capitalism, Singapore in little more than a generation moved “from third world to first,” as a memoir of founding father Lee Kuan Yew puts it.

In truth, Singapore — a mix of majority Chinese and smaller Malay and Indian communities — wasn’t quite as backward upon independence as its boosters claim. The city-state’s economic development was unmatched by individual political liberties. The nanny state admirably manicured Singapore but it had little patience for dissonant voices. Still, as TIME’s anniversary special on Singapore reports in this week’s magazine, the “little red dot” claims outsized geopolitical influence in the region and is a magnet for migrants worldwide.

The rapid influx of foreigners into Singapore, though, has frustrated the electorate, which punished the ruling People’s Action Party in 2011 polls. (The party, now headed by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, Lee Kuan Yew’s son, still garnered a majority of votes.)

The government was trying to make up for a precipitous decline in Singaporean fertility by importing more than 1 million people into a nation that now has a current population of roughly 5.5 million. Yet there was a sense that the flood of foreigners, particularly mainland Chinese, was straining the city-state’s much-vaunted public works, pushing up property prices and diluting the national character. “We are all sons and daughters of immigrants,” says Manu Bhaskaran, an economist whose forebears came from southern India. “But this immigration policy has made us addicted to cheap labor, and it was done without providing enough infrastructure to cope.”

As Singapore gears up to celebrate the 50th anniversary of its independence, the city-state once dismissed as a “little red dot” at the midpoint of regional maps now serves as the epicenter of Asian-style development. By combining Confucian values with state-sponsored capitalism, Singapore in little more than a generation moved “from third world to first,” as a memoir of founding father Lee Kuan Yew puts it.

In truth, Singapore — a mix of majority Chinese and smaller Malay and Indian communities — wasn’t quite as backward upon independence as its boosters claim. The city-state’s economic development was unmatched by individual political liberties. The nanny state admirably manicured Singapore but it had little patience for dissonant voices. Still, as TIME’s anniversary special on Singapore reports in this week’s magazine, the “little red dot” claims outsized geopolitical influence in the region and is a magnet for migrants worldwide.

The rapid influx of foreigners into Singapore, though, has frustrated the electorate, which punished the ruling People’s Action Party in 2011 polls. (The party, now headed by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, Lee Kuan Yew’s son, still garnered a majority of votes.)

The government was trying to make up for a precipitous decline in Singaporean fertility by importing more than 1 million people into a nation that now has a current population of roughly 5.5 million. Yet there was a sense that the flood of foreigners, particularly mainland Chinese, was straining the city-state’s much-vaunted public works, pushing up property prices and diluting the national character. “We are all sons and daughters of immigrants,” says Manu Bhaskaran, an economist whose forebears came from southern India. “But this immigration policy has made us addicted to cheap labor, and it was done without providing enough infrastructure to cope.”

Over the centuries Singapore has proven a master of reinvention. As a British colony, the island grew rich from a trade in rubber and tin. After independence, the country’s port — now the world’s second-largest by certain measures — again proved invaluable as a waystation for the products being churned out by East Asia’s export-led economies. To move up the value-added chain, Singapore also began focusing on developing its own oil-refining and IT industries, as well as luring foreign banks and other global companies to its shores. The city-state has reclaimed acres of land to provide space for the regional headquarters of these multinationals, as well as for a casino meant to lure deep-pocketed Chinese tourists.

Singapore’s latest round of reinvention will require the island to yet again leverage its geography, at a time when tensions are growing between the U.S. and China — both friends to the city-state. But Singapore’s greatest feat at age 50 will be to unleash the potential of its biggest asset: its people. Highly educated and boasting some of the world’s highest per-capita incomes, Singaporeans may no longer be quite so obedient. If the nation is to fulfill its ambition to transform into an innovation hub, perhaps that’s just as well. The question is whether the ruling party, the longest serving in the developed world, also sees it that way. On July 10, TIME spoke with Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong about the nation at the half-century mark, his reading of regional geopolitics and whether the son of Singapore’s founding father was ever a rebellious teenager. Excerpts below:

What is the single-biggest challenge Singapore faces?

If you are looking at 10 years, getting the economy to the next level is a very big challenge. If we don’t get to the next level then we will have malaise and angst and even disillusionment, which you see in many developed countries. And in 25 years, if we can’t get our demography balance between our births and immigration of foreign workers, then we will be in a very tight spot like the Japanese are. If you take a 50-year timeframe, then the most important thing is the sense of national identity, because before you can make any policies and get people to say “I want to do this or the other,” people must feel that we are Singaporeans and we want to be together and we are different from others and we are special. Keeping that sense of unity and specialness over the long term is critical.

What do you mean by the next economic level?

We are at 30% students going through our universities and we are going to push that up to 40%. A lot of people go to university outside of our state system — they may do part-time courses, they go to Australia or Britain, all kinds of degrees. When they come back they expect to have PMET jobs — Professional, Managers, Executives, Technical. [We need] an economy that can generate that quality of jobs and uplift those who didn’t go to university so you don’t have a wide gap between the tertiary-educated and the rest, which has happened in America where a college degree now makes a big difference compared to a high-school leaver. You cannot do that without growth and you cannot get growth just by expansion with bodies because I don’t have that many more bodies and I can’t bring in a lot more bodies without bursting at the seams. So I need qualitatively different jobs, qualitatively a more efficient overall economy. My infrastructure must run brilliantly. My whole system must be different from what you can get anywhere else in Asia. The others are catching up. So even as the others step into where we are, we have to be at the next level.

People overseas talk a lot about the Singapore model of development…

I don’t think there is a model but there is an approach that we have applied in Singapore. A government that is pragmatic—it looks for solutions that work, rather than starting out from any ideological presumptions. It depends to a considerable degree on the free market because markets make economies efficient. But at the same time, the government is not shy to play a very active role — in public housing, education, healthcare, infrastructure. You are talking about a society and a political system where we are trying to work toward a middle ground rather than division between economic interest groups or racial groups or rich and poor or left- and right-wing. Basically most people benefit from the system and uphold the system … We have come these 50 years and we have kept our mission substantially intact. That’s quite an achievement.

Can this Singapore approach be emulated by other countries?

What we can do in Singapore may not be doable elsewhere. Some things you know you need, you want efficient government, you want clean government, you want to do away with corruption, you must educate your people. You want to get housing and so on. All these are not such secrets, not so special to Singapore. But how you can do it is very difficult and very different. For example, we have worked very hard to bring together our government, our unions and our employers. We call it a tripartite relationship. It’s a bit of an ungainly term, but it means something valuable to us. We bargain, we discuss, in the end there is a significant amount of give-and-take and mutual confidence and trust built up over many bargainings and many experiences shared — ups and downs. And so, we have the trust to move forward.

Moving forward, the Singapore approach naturally will evolve. How do you see that change happening?

When we started out, backs were to the wall. Today, our backs are not to the wall, so it does not appear to be a life-and-death matter and yet, in fact, it continues to be an act of will to be where we are. The tactics we were able to use in the 1960s, 1970s — let’s have a campaign, mobilize everybody and, therefore, social pressure — stop littering, or stop spitting, or be courteous to one another: I am not sure that kind of approach will work anymore. Secondly, there are more interests and preoccupations. If you look at the young people today, they are passionate about all kinds of courses. We have dog-lovers, nature-lovers, those who are pursuing arts, we have quite many who are involved in religious activities through their church. Even the Buddhist groups are active. So there is a much more variegated society and to find that common ground to stand together and make unity in diversity more than a slogan; that’s quite a challenge. The conventional wisdom in the West is that you let a hundred flowers bloom and everything will be happiness and sweetness and light. We don’t quite believe that. You have to tend the garden to make it flower and the challenge will be how we can do that while having a greater degree of free play and yet not have things end up in a bad outcome.

You have said that the politics will change. But the government has also been criticized for being paternalistic, for stressing society and family over the individual…

That’s the standard liberal line.

[Same old criticism of Singapore]

It is. You say you are aware of the changing needs and aspirations particularly of the youth. At the same time, very recently, the courts have convicted a 16-year-old for a video and a blogger for a post. How do you reconcile this?

There is always a balance between freedom and the rule of law; freedom is never totally unlimited. It operates within certain constraints. In our society, which is multiracial and multi-religious, giving offense to another religious or ethnic group, race, language or religion, is always a very serious matter. In this case, he’s a 16-year-old, so you have to deal with it appropriately because he’s of a young age. But even in the recent couple of years, we have seen many cases where one Internet post injudiciously can overnight cause a humongous row, everybody gets offended because they said something bad about Christians, said something about the Buddhists, some Chinese said something about the Malays. It can be a very big problem. So we have to take this seriously. With the Internet, it’s harder because it’s easier to give offense and easier to take offense and if we get agitated every time somebody gives offense, then we’ll spend our lives very agitated. And yet, it is necessary with the Internet to be more restrained and to learn where the limits are.

[A better internet]

On the other case of defamation, you have freedom of speech, you can criticize the government as much as you like on policy, on substance, on competence. But if you make a defamatory allegation that the Prime Minister is guilty of criminal misappropriation of pension funds of Singaporeans, that’s a very serious matter. If it’s true, the Prime Minister should be charged and jailed. If it’s not true, the matter must be clarified and the best way to do that is by settling in court. If it’s untrue, it will be shown so. If it’s true, the Prime Minster will be destroyed. Somebody says very bad things about me, I don’t clear my name — do I deserve to be here or not? In an Asian society, particularly, if the leader can’t maintain his standing, he doesn’t deserve to be there. He will soon be gone.

[Over-rated (Freedom of Expression)]

You’ve got a big immigrant population that has helped the economy, that has probably enriched society, but that has also created resentment. How do you strike a balance between the local and immigrant population? What are the pitfalls of too much immigration?

It’s a big challenge, it’s very difficult to do. Ideally, no, not only ideally, but essentially, we must have a Singapore core in the society because if you don’t have that Singapore core, you can top up the numbers, but you are no longer Singapore. It doesn’t feel Singapore, it isn’t Singapore. So you really need a solid core of Singaporeans with quite deep roots here, born here or spent many years here and you need enough children born from Singaporeans here, Singaporean-born so that in the next generation it can continue and people know the society, do National Service here, school, work and so on. And then we can top up with immigrants in a controlled number. We can complement it with foreign workers who are not immigrants but come here, they work, their job is done, they go home.

Yet you have been quite successful in forging a national identity…

It is not so simple. If you are Japanese, there’s no doubt that you’re Japanese, you speak Japanese, you speak English with an accent most of the time and you will feel most comfortable in Japan. If you’ve grown up elsewhere as a Japanese, you go home, it doesn’t fit. Many Japanese diplomats have that problem with their children … In Singapore, we have race, language and religion to add to the mix. Language may be less, although the language identity of the Malays, or for that matter, of the Indians, will still be there and of a significant proportion of the Chinese population, that they want to keep that part of them even if their working language is English. The religion is a stronger motivator than ever before. It’s not just in Singapore, but all over the word, Christians, Buddhists, Muslims, people take their religions very, very seriously. You can have other divisions. It can be values — LGBT issues can become a divisive issue. It can be based on ethnic and external relations. We are mostly Chinese, China becomes a great power, what is the impact on our people’s thinking and perspectives on the world and how does that impact on the Malays and the Indians who are non-Chinese? How will they feel if you find yourself tilted toward China? Will that not cause tensions at least? Divisions, we hope not. You cannot assume that people will automatically say “I am a Singaporean” and there’s no further sub-division or sub-classification that matters.

[Being Singaporean]

Could a non-Chinese be Prime Minister?

It could be, it depends on the person. You must have the right person — you must have the politics worked out, you must be able to connect both with the Chinese as well as the non-Chinese population. With the new generation, the chances are better. With the present generation, even today, if you go to the constituencies and you talk on the ground, you mingle, most of the time you would be speaking some Chinese. Even with the younger ones, a significant proportion of them would be more comfortable speaking in Mandarin because that’s their home conversational language. I have young people who write to me in Chinese. I am quite surprised, but they still exist. So, on the ground, if you cannot communicate in Mandarin and if they feel you cannot communicate in Mandarin, that’s a minus. That’s the ground reality.

You mentioned the increase in religiosity not just in Singapore but also in the rest of the world. What are the ramifications?

You could say it’s because of the stresses of modern living. You could also say it’s because these are global trends that have grown elsewhere and our people are influenced by that. If you look at our Christian churches, the Protestants particularly, they have very close links with Protestant churches elsewhere in America, even in Africa. And if you look at the Muslims, that’s worldwide. Maybe it’s Saudi Arabia, maybe it’s Iran, maybe it’s the madrassahs in Pakistan, but it’s worldwide, it’s a very, very strong Muslim revival.

Overall, religion is a good thing. If we were a godless society, we would have many other problems. Religion is a good thing provided we are able to bridge the differences between our different faiths, provided there’s give-and-take, provided we are able to get along together and not offend one another by aggressive proselytization, by denigrating other faiths, by being separate and, therefore, having suspicions of one another, which can easily happen. So you have to make an extra effort to develop that trust and to work together, which we have been doing.

Islam — you have an extra dimension because of the…

Because of the jihadist problem.

There’s a growing militancy in the Middle East and many of your neighbors are either Muslim-majority or have sizable Muslim populations. There have been cases of Indonesians, also Malaysians, going to fight for ISIS…

Singaporeans too.

So do you worry about a jihadist foothold in Southeast Asia?

We are very concerned about the jihadist terrorist threat. We had to take it very, very seriously since around 9/11 when we first discovered the Jemaah Islamiyah [JI] group here, which was intending to set off six or seven truck bombs and had got quite far advanced before we intervened and broke them up. The problem is endemic in the region. The Malaysians are having people getting converted and going and they’ve just arrested another couple of people. The Indonesians have hundreds who have gone and they are not just fighters going but families migrating to live under an ideal Islamic caliphate and they come back and when they come back, they are a problem. The ISIS objective is to set up a wilayat — a province of the worldwide Islamic caliphate — in Southeast Asia. I think that’s ridiculous. But there are a lot of corners of Southeast Asia where the government doesn’t run very strongly — in southern Thailand, southern Philippines, corners of Indonesia — and it’s not so far-fetched if they establish a foothold in one of these areas, as JI had a foothold in the southern Philippines. And if they have a little base there, you have a training camp there and then you claim that you are master of some territory and then people start to make their way there — that’s a different level of threat.

You can control within your own borders. But are you satisfied with the efforts made by neighboring governments to combat this potential threat?

We can control within our borders as long as we know we have information. We cooperate with our neighbors, we cooperate with other governments and security agencies, they share their information with us and us with them, and it’s very helpful. But when somebody radicalizes himself, we may not know because there is no network, there’s no trail. It’s between him and his computer and some video on the other end, or perhaps a contact he has established on the other end. If we are lucky, we may find out. If we are not lucky, well, he can get quite far. That’s a problem. Our neighbors have a much harder problem because they are much bigger countries. One police chief of one of my neighbors came to visit Singapore and we had a conference and he said to me, our difficulty is that 90% of our population is Muslim. And, therefore, it is very difficult for them to act against the terrorists without antagonizing the 90% who are Muslims. Not that the 90% of Muslims are terrorists, but how do you winkle this part out without causing collateral damage and political difficulty?

Lee Kuan Yew once told us that what China’s leaders called their nation’s “peaceful rise” was a contradiction in terms. Since then, China has become even more powerful and influential. Is the Chinese leadership overreaching? Is it, through its growing power, growing might, alienating its neighbors? Is it forfeiting its goodwill?

Every year the Chinese Premier attends the ASEAN Leaders’ Meeting. He comes with a very carefully thought-out set of things which he wants to do with ASEAN and he makes sure that there’s a little Christmas present for everybody and everybody sees that this is a relationship from which they can benefit. So the Chinese want their neighbors to be their friends. At the same time, on something like the South China Sea, they want their interests to prevail. [But] if they push too hard, there’ll be a pushback and even if you can’t resist the pressure because one country is big and the other is small, over the long term dominance based on just overwhelming power is not really an adequate basis for influence, much less soft power.

In the case of South China Sea, you do not have a claim…

We don’t have a claim, but we have an interest in seeing it managed and settled peacefully and in accordance to international law and UNCLOS [United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea]; we also have an interest in freedom of navigation and overflight.

So what are you telling the Chinese?

We’re telling the Chinese that you have your rights, you are entitled to assert your rights, but at the same time, you have to look at the broader relationship and calculate that how you handle the South China Sea issue will be seen as one marker of how a powerful China will assert its place in the world.

Do they get it?

I do not know, but I’ve said that to them … There’s some internal dynamics involved. The PLA [People’s Liberation Army] will have a harder line; it is influential in their deliberations. I don’t know where in their system a soft line will come, but I think the Chinese population, if you ask them instinctively, I don’t think their instincts would be to say “let’s take a gentle approach because this will help us be seen as a benign panda.” I think that’s the mood in China now because the country has done well, it has prospered, it’s stronger, it has got an aircraft carrier. They think it’s time to stand up and assert their rights. They have been humiliated for too long.

The building, the expansion of reefs into full-fledged islands — what does that do to the delicate balance?

It’s creating facts on the ground.

You have spoken in Beijing about the need not to underestimate the U.S, not to overestimate the U.S. decline. Does China understand that?

The Chinese understand that it would be very many years before they can catch up to the Americans in terms of level of technology or science or defense. But they may think that with American elections coming and the administration approaching its last phase, that there’s a window of opportunity when the Americans are distracted elsewhere, that they will have greater freedom of maneuver. These are tactical calculations.

And what advice are you giving the Americans about what they should be doing in Asia and how committed they should be?

You have a lot of friends here, you have a lot of investments here, you have a lot of interests here and it’s foolish of you not to look to them. When you make decisions, you have to think about that, and not just your congressional district.

Do you get heat from Beijing that Singapore is too pro-U.S. or reflects too much the American point of view?

Every country would like their friends to stand closer to them on policies and issues, but I think they understand the reason why we take the stand we do. As a small country, we have to have our own independent stand, otherwise nobody will take us seriously.

You’ve talked a lot about the philosophy and character of Singapore. So much of that was shaped by Lee Kuan Yew. How much of your own thinking on politics, culture, world affairs, life itself, is influenced by him?

A great deal. I mean, he’s my father, I grew up learning from him, I worked under him when he was Prime Minister, with him in the Cabinet these last 30 years until he died. So it’s bound to be a very deep influence. Yet at the same time, it’s a different world and he knew that and he was very good at preparing for Singapore to move on and not be stuck in the Lee Kuan Yew mode. Only very rarely did he assert a strong view and asked us to please rethink something. But otherwise, he allowed an evolution to take place so that Singapore would carry on beyond him. And if you watch what happened when he died, we had an enormous outpouring of sorrow, but Singapore carried on. The stock market didn’t crash, investors didn’t panic, confidence was maintained.

Were you a rebellious teenager?

In my generation we didn’t think in those terms. You don’t always agree with your parents, but I never had long hair or wore bell-bottoms.

Besides Lee Kuan Yew, when you look at the pantheon of world leaders, both current and past, who are the other great men and women whom you admired?

Lula [Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva] in Brazil was remarkable — very little education, left-wing firebrand, mobilized a nation, became President and was able to not only to get people to support him, but actually pursue very sensible policies that promoted growth and development and improve people’s lives. He was able to make that transition from being a firebrand and a revolutionary to somebody who can cause growth and development. I thought it was remarkable. I met him and I was very impressed. Then you look at Angela Merkel; she’s a very careful politician. She’s got many constraints, but she’s well-established in her home base and deeply respected outside of Germany and not only in Europe. And if you talk to her, I mean, she’s not somebody aloof and overbearing. Very personable frau, but a very capable and steady woman. She will not cause a revolution, but she knows what she needs to do as Bundeskanzler [Chancellor of Germany].

You’ve mentioned two leaders from liberal democratic nations.

I only met King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia once and he was already in his late 80s. I was quite impressed because you think of this as a society where people scrape and bow and I’ve seen some other Arab monarchs where people literally scrape and bow and prostate themselves. But I called on him and he had his ministers in attendance and we had a conversation, him with me and then he brought the ministers into the conversation. I watched them, and the ministers addressed him, at most primus inter pares. It was a very easy, confident, relaxed relationship. There’s a conversation, there’s a respectful response. He made reforms within what’s possible in the society. To do that at the age of 80-something, that’s not easy.

What is your sense of Xi Jinping?

I have met him quite a number of times. I have chatted with him before he became President and then even after, called on him, just talked to him sometimes over dinner. He masters his brief, he knows what he wants, and he will discuss many things with you. When people think of a Communist country with a leader, you will think of somebody like Brezhnev or Tito. [Xi] is not like that. He’s not a pushover at all. He knows what he wants, and there is a curiosity about the world.

No comments:

Post a Comment