Two articles on the question of gluten in diet. Who should avoid it and is it healthier to avoid if even if you are not sensitive to it.

Gluten - not a problem until you make it your first world problem, because, hey, you need to feel like a victim too... or something. I'm not a psychologist. So I don't know what's your problem. But I do know that if you do not have celiac disease, gluten is not one of your problems.

Researchers Who Provided Key Evidence For Gluten Sensitivity Have Thoroughly Shown That It Doesn't Exist

JENNIFER WELSH,

BUSINESS INSIDER

19 AUG 2015

In one of the best examples of science working, a researcher who provided key evidence of (non-celiac disease) gluten sensitivity recently published follow-up papers that show the opposite.

The paper came out last year in the journal Gastroenterology. Here’s the backstory that makes us cheer: The study was a follow up on a 2011 experiment in the lab of Peter Gibson at Monash University in Australia. The scientifically sound - but small - study found that gluten-containing diets can cause gastrointestinal distress in people without celiac disease, a well-known autoimmune disorder triggered by gluten. They called this non-celiac gluten sensitivity.

Gluten is a protein composite found in wheat, barley, and other grains. It gives bread its chewiness and is often used as a meat substitute: If you’ve ever had 'wheat meat', seitan, or mock duck at a Thai restaurant, that’s gluten.

Gluten is a big industry: 30 percent of people want to eat less gluten. Sales of gluten-free products are estimated to hit $US15 billion by 2016.

Although experts estimate that only 1 percent of Americans - about 3 million people - actually suffer from celiac disease, 18 percent of adults now buy gluten-free foods.

Since gluten is a protein found in any normal diet, Gibson was unsatisfied with his finding. He wanted to find out why the gluten seemed to be causing this reaction and if there could be something else going on. He therefore went to a scientifically rigorous extreme for his next experiment, a level not usually expected in nutrition studies.

For a follow-up paper, 37 self-identified gluten-sensitive patients were tested. According to Real Clear Science’s Newton Blog, here’s how the experiment went:

"In contrast to our first study… we could find absolutely no specific response to gluten," Gibson wrote in the paper. A third, larger study published this month has confirmed the findings.

It seems to be a 'nocebo' effect - the self-diagnosed gluten sensitive patients expected to feel worse on the study diets, so they did. They were also likely more attentive to their intestinal distress, since they had to monitor it for the study.

On top of that, these other potential dietary triggers - specifically the FODMAPS - could be causing what people have wrongly interpreted as gluten sensitivity. FODMAPS are frequently found in the same foods as gluten. That still doesn’t explain why people in the study negatively reacted to diets that were free of all dietary triggers.

You can go ahead and smell your bread and eat it too. Science. It works.

James Hamblin

May 16, 2016

May is Celiac-Disease Awareness Month. Which might seem unnecessary, if the superfluity of “gluten free” labels and advertisements were any indication of people’s awareness of the disease.

Gastroenterologist Norelle Rizkalla Reilly believes it’s quite clearly not. She directs the Celiac Disease Center’s pediatric program at Columbia University. Her understanding of public misconceptions comes not just from daily immersion in the world of gluten-related immune disorder, but from a careful analysis of the true window into our souls: our Google histories.

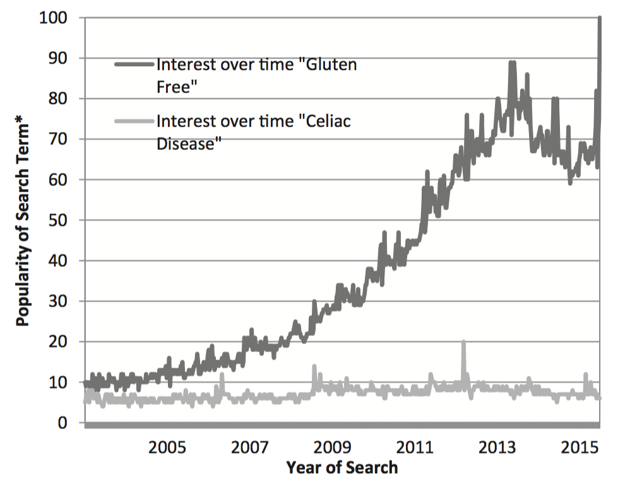

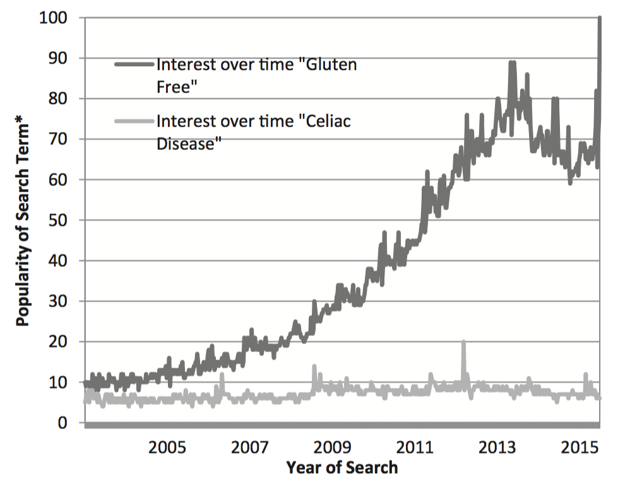

On Friday she published the chart below in the Journal of Pediatrics:

Google Search Term Popularity: "Celiac Disease" Versus "Gluten Free" (Reilly / Journal of Pediatrics)

(Reilly / Journal of Pediatrics)

“I thought that was particularly illustrative of how the popularity of this diet has increased, totally out of proportion to any sense of awareness of celiac disease,” Reilly told me, an air of exhaustion about her after a “particularly grueling” day in the clinic.

There the foundation of her practice is careful, deliberate implementation of a gluten-free diet, so she has been concerned to see that therapy slip out of its serious medical context. For people with celiac disease, avoiding gluten is a medical necessity. Done carefully, it can take a person from incapacitated to symptom-free in short order, as the lining of the small intestine returns to normal.

Like most medical interventions, though, this one has not been shown (in placebo-controlled studies) to benefit people who do not have the disease. Celiac disease is known to affect about one percent of people. Yet in a global survey of 30,000 people last year, fully 21 percent said that “gluten free” was a “very important” characteristic in their food choices. Among Millennials, the number is closer to one in three. The tendency to “avoid gluten” persists across socioeconomic strata, in households earning more than $75,000 just the same as those earning less than $30,000, and almost evenly among educational attainment. The most common justification for doing so: “no reason.”

In the medical journal, Reilly’s message is that physicians should be educating people that this is not okay. “You have the gluten-free industry speaking with a megaphone,” she said, “and we're trying to do our part to put accurate information into circulation.”

It’s in that context that she addresses the many risks that come with taking on a gluten-free diet when it is not medically warranted. That includes studies that have found increased rates of metabolic syndrome among people who switch to a gluten-free diet, presumably due to poor nutritional quality of gluten-free replica products. Other studies have reported people developing deficiencies in folate, thiamine, and iron, which are added to grain products by law. When researchers in Spain compared 206 gluten-free food products to their traditional gluten-containing counterparts, the team found “marked differences” in the nutrient and caloric contents. “This may represent a nutritional concern for celiac patients,” the researchers concluded, “but it may also be a problem for non-celiacs who consume gluten-free rendered foods.”

For parents concerned about arsenic in rice, Reilly regularly advises that many gluten-free products replace grain products with rice (which she sometimes refers to as “secret rice”). To minimize risk of arsenic exposure, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that kids simply eat a diverse diet. Eliminating all foods that contain gluten makes that goal only more difficult.

Among people of all ages, she notes, several small studies have now found deterioration in quality of life after the switch. For children especially, imposing a gluten-free diet can be socially isolating. In the journal Pediatrics, kids with celiac disease who attended a week-long gluten-free camp, where every food was gluten free by default, “demonstrated improvement in well-being, self-perception, and emotional outlook”—which seemed to be because the environment “alleviate[d] stress and anxiety around food and social interactions.”

Life is not gluten-free camp, though. In the real world, gluten-free versions of foods are most often more expensive than the standard formulations, as well. (An especially pointed factor for the 20 percent of households earning less than $30,000 annually and yet worrying about procuring gluten-free products.)

“We obviously have a lot of patients who need to be on a gluten-free diet,” Reilly added, “and I don't mean to alarm those individuals.”

Given the disproportionate number of people who are eating this way without reason, though, there is cause for alarm. Especially among the many people who now mistakenly and blindly conflate “gluten free” and “healthy.” And among those who believe they may have celiac disease but do not get tested. Proper diagnosis is crucial not only to be certain that avoiding gluten and incurring the costs and risks above is truly necessary, but because other conditions sometimes go hand-in-hand with celiac. Those include the skin condition dermatitis herpetiformis, lymphoma, anemia, depression, liver disease, and osteopenia (weak bones). Having a proper diagnosis may inform future medical care not just for patients, but for their families.

As Reilly put it, resolutely but without alarm, “Anything that could potentially derail detection of this disease, including starting the diet on one's own, should be avoided.”

[So you or a friend you know may be on a gluten-free diet in the belief that you are (or your friend is) gluten sensitive or gluten intolerant, although you do not have celiac disease or other medical diagnosis supporting that belief.

So what are you to do then.

Am I telling you to get off your high hypochondriac horse and smell the horse poo cos you don't have gluten intolerance.

God, no.

Please believe what you want. Far be it for me to tell you what to believe or how to spend your money (on gluten free products).

And if it is your friend who is interested in a gluten-free diet (or is already on one), please do not tell him to stop. You may refer this piece to him (or her) and leave him or her to decide for himself/herself.

It may well be that he/she will have reasons (or make up reasons) why they should continue on their gluten-free diet. Unless they are borrowing money from you to maintain their gluten-free diet, it should not matter to you. If they are trying to borrow money from you to maintain their gluten-free diet, show them this piece, tell them no, unless they produce a letter from a doctor ascertaining that they have celiac disease or otherwise need a gluten free diet.

Even then, you can still say no.]

In one of the best examples of science working, a researcher who provided key evidence of (non-celiac disease) gluten sensitivity recently published follow-up papers that show the opposite.

The paper came out last year in the journal Gastroenterology. Here’s the backstory that makes us cheer: The study was a follow up on a 2011 experiment in the lab of Peter Gibson at Monash University in Australia. The scientifically sound - but small - study found that gluten-containing diets can cause gastrointestinal distress in people without celiac disease, a well-known autoimmune disorder triggered by gluten. They called this non-celiac gluten sensitivity.

Gluten is a protein composite found in wheat, barley, and other grains. It gives bread its chewiness and is often used as a meat substitute: If you’ve ever had 'wheat meat', seitan, or mock duck at a Thai restaurant, that’s gluten.

Gluten is a big industry: 30 percent of people want to eat less gluten. Sales of gluten-free products are estimated to hit $US15 billion by 2016.

Although experts estimate that only 1 percent of Americans - about 3 million people - actually suffer from celiac disease, 18 percent of adults now buy gluten-free foods.

Since gluten is a protein found in any normal diet, Gibson was unsatisfied with his finding. He wanted to find out why the gluten seemed to be causing this reaction and if there could be something else going on. He therefore went to a scientifically rigorous extreme for his next experiment, a level not usually expected in nutrition studies.

For a follow-up paper, 37 self-identified gluten-sensitive patients were tested. According to Real Clear Science’s Newton Blog, here’s how the experiment went:

Subjects would be provided with every single meal for the duration of the trial. Any and all potential dietary triggers for gastrointestinal symptoms would be removed, including lactose (from milk products), certain preservatives like benzoates, propionate, sulfites, and nitrites, and fermentable, poorly absorbed short-chain carbohydrates, also known as FODMAPs. And last, but not least, nine days worth of urine and faecal matter would be collected. With this new study, Gibson wasn’t messing around.The subjects cycled through high-gluten, low-gluten, and no-gluten (placebo) diets, without knowing which diet plan they were on at any given time. In the end, all of the treatment diets - even the placebo diet - caused pain, bloating, nausea, and gas to a similar degree. It didn’t matter if the diet contained gluten. (Read more about the study.)

"In contrast to our first study… we could find absolutely no specific response to gluten," Gibson wrote in the paper. A third, larger study published this month has confirmed the findings.

It seems to be a 'nocebo' effect - the self-diagnosed gluten sensitive patients expected to feel worse on the study diets, so they did. They were also likely more attentive to their intestinal distress, since they had to monitor it for the study.

On top of that, these other potential dietary triggers - specifically the FODMAPS - could be causing what people have wrongly interpreted as gluten sensitivity. FODMAPS are frequently found in the same foods as gluten. That still doesn’t explain why people in the study negatively reacted to diets that were free of all dietary triggers.

You can go ahead and smell your bread and eat it too. Science. It works.

The Harm in Blindly ‘Going Gluten Free’

It is not an innocuous decision.James Hamblin

May 16, 2016

May is Celiac-Disease Awareness Month. Which might seem unnecessary, if the superfluity of “gluten free” labels and advertisements were any indication of people’s awareness of the disease.

Gastroenterologist Norelle Rizkalla Reilly believes it’s quite clearly not. She directs the Celiac Disease Center’s pediatric program at Columbia University. Her understanding of public misconceptions comes not just from daily immersion in the world of gluten-related immune disorder, but from a careful analysis of the true window into our souls: our Google histories.

On Friday she published the chart below in the Journal of Pediatrics:

Google Search Term Popularity: "Celiac Disease" Versus "Gluten Free"

(Reilly / Journal of Pediatrics)

(Reilly / Journal of Pediatrics)“I thought that was particularly illustrative of how the popularity of this diet has increased, totally out of proportion to any sense of awareness of celiac disease,” Reilly told me, an air of exhaustion about her after a “particularly grueling” day in the clinic.

There the foundation of her practice is careful, deliberate implementation of a gluten-free diet, so she has been concerned to see that therapy slip out of its serious medical context. For people with celiac disease, avoiding gluten is a medical necessity. Done carefully, it can take a person from incapacitated to symptom-free in short order, as the lining of the small intestine returns to normal.

Like most medical interventions, though, this one has not been shown (in placebo-controlled studies) to benefit people who do not have the disease. Celiac disease is known to affect about one percent of people. Yet in a global survey of 30,000 people last year, fully 21 percent said that “gluten free” was a “very important” characteristic in their food choices. Among Millennials, the number is closer to one in three. The tendency to “avoid gluten” persists across socioeconomic strata, in households earning more than $75,000 just the same as those earning less than $30,000, and almost evenly among educational attainment. The most common justification for doing so: “no reason.”

In the medical journal, Reilly’s message is that physicians should be educating people that this is not okay. “You have the gluten-free industry speaking with a megaphone,” she said, “and we're trying to do our part to put accurate information into circulation.”

It’s in that context that she addresses the many risks that come with taking on a gluten-free diet when it is not medically warranted. That includes studies that have found increased rates of metabolic syndrome among people who switch to a gluten-free diet, presumably due to poor nutritional quality of gluten-free replica products. Other studies have reported people developing deficiencies in folate, thiamine, and iron, which are added to grain products by law. When researchers in Spain compared 206 gluten-free food products to their traditional gluten-containing counterparts, the team found “marked differences” in the nutrient and caloric contents. “This may represent a nutritional concern for celiac patients,” the researchers concluded, “but it may also be a problem for non-celiacs who consume gluten-free rendered foods.”

For parents concerned about arsenic in rice, Reilly regularly advises that many gluten-free products replace grain products with rice (which she sometimes refers to as “secret rice”). To minimize risk of arsenic exposure, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that kids simply eat a diverse diet. Eliminating all foods that contain gluten makes that goal only more difficult.

Among people of all ages, she notes, several small studies have now found deterioration in quality of life after the switch. For children especially, imposing a gluten-free diet can be socially isolating. In the journal Pediatrics, kids with celiac disease who attended a week-long gluten-free camp, where every food was gluten free by default, “demonstrated improvement in well-being, self-perception, and emotional outlook”—which seemed to be because the environment “alleviate[d] stress and anxiety around food and social interactions.”

Life is not gluten-free camp, though. In the real world, gluten-free versions of foods are most often more expensive than the standard formulations, as well. (An especially pointed factor for the 20 percent of households earning less than $30,000 annually and yet worrying about procuring gluten-free products.)

“We obviously have a lot of patients who need to be on a gluten-free diet,” Reilly added, “and I don't mean to alarm those individuals.”

Given the disproportionate number of people who are eating this way without reason, though, there is cause for alarm. Especially among the many people who now mistakenly and blindly conflate “gluten free” and “healthy.” And among those who believe they may have celiac disease but do not get tested. Proper diagnosis is crucial not only to be certain that avoiding gluten and incurring the costs and risks above is truly necessary, but because other conditions sometimes go hand-in-hand with celiac. Those include the skin condition dermatitis herpetiformis, lymphoma, anemia, depression, liver disease, and osteopenia (weak bones). Having a proper diagnosis may inform future medical care not just for patients, but for their families.

As Reilly put it, resolutely but without alarm, “Anything that could potentially derail detection of this disease, including starting the diet on one's own, should be avoided.”

[So you or a friend you know may be on a gluten-free diet in the belief that you are (or your friend is) gluten sensitive or gluten intolerant, although you do not have celiac disease or other medical diagnosis supporting that belief.

So what are you to do then.

Am I telling you to get off your high hypochondriac horse and smell the horse poo cos you don't have gluten intolerance.

God, no.

Please believe what you want. Far be it for me to tell you what to believe or how to spend your money (on gluten free products).

And if it is your friend who is interested in a gluten-free diet (or is already on one), please do not tell him to stop. You may refer this piece to him (or her) and leave him or her to decide for himself/herself.

It may well be that he/she will have reasons (or make up reasons) why they should continue on their gluten-free diet. Unless they are borrowing money from you to maintain their gluten-free diet, it should not matter to you. If they are trying to borrow money from you to maintain their gluten-free diet, show them this piece, tell them no, unless they produce a letter from a doctor ascertaining that they have celiac disease or otherwise need a gluten free diet.

Even then, you can still say no.]

No comments:

Post a Comment